A Playground, Not a Fortress

By Amity Shlaes

This essay is adapted from Amity Shlaes’s regular column “The Forgotten Book,” which she pens for “Capital Matters” as a fellow of National Review Institute.

Any administration has to place bets on how to prepare for the next war. The Defense Department’s Fiscal 2026 budget proposal allocates $25 billion for a Golden Dome, a version of Israel’s Iron Dome, to protect Americans from missiles. Already the DOD’s “acquisition community”—that lovable euphemism for bureaucrats on the buy side—is surrounded by companies vying for Golden Dome contracts. China poses a maritime threat. President Trump followed many a president with plans to shore up the Merchant Marine so commercial ships can back up our military in conflicts.

But the truth is we know little about the next war. And even less about the war that comes after that. That’s why building up a grand defense can’t suffice. Hitler’s panzers rolled right around the Maginot Line, through Belgium.

What we do know is that a strong American economy is its own Golden Dome. The more economically formidable the United States, the less likely others are to assail us. Wars can be waiting games, and stronger economies have the resources to outwait the other side. But what makes an economy strongest?

The answer, so counterintuitive to the collective war brain, is that the strongest economy is less fortress than playground. An economic playground that lures all kinds of innovators, especially individuals and small companies, can yield great benefits for the U.S., whether in immediate conflict or wars far in the future.

Why a playground? Because in peace as in war, the government is a rotten guesser. The business bets that a peacetime government places don’t yield optimal growth—green technology being just one example. Stunning growth comes from the ideas of outsiders, the lesser-knowns. Rather than target certain sectors and try to engineer results, therefore, the government should aim to make overall conditions more inviting.

What’s more, war’s course is often turned by what some call a “technological surprise,” an innovation so unexpected that it flummoxes the enemy. Often enough, the surprise comes from an outside innovator. Back in 2014, when war between Ukraine and Russia broke out, no one expected that Elon Musk and Starlink would be playing such a role in the conflict today.

Play Pays Off

The long-term payoff of a playful economy is clear when you survey the record of the past century, starting with the contemplative decade after World War I. History books paint the 1920s as thoughtlessly isolationist. But this picture is off. Even then voters knew that one world war meant another could follow. How to prepare? The government did some direct prep, devoting, in those years, a full quarter of the federal budget to the military. That share rises to half when you count military-related expenses, such as pensions for veterans.

Yet lawmakers in the 1920s also recognized that there were larger choices to be made. Perhaps America needed to build a great standing army. Or perhaps not. “It seems obvious that there are two theories with regard to a military establishment,” said Senator John S. Williams of Mississippi in 1921. “One would be to establish an army to whip anybody.... In order to do that we would need about 2 million men on a peace establishment, or a million at any rate.” The other path, the senator suggested, was “to pursue our traditionary policy of conserving the financial resources of the people during times of peace.”

Woodrow Wilson’s administration had commandeered more or less the entire economy in the war effort, raising the top income tax rate to 77 percent, shutting down the stock market for months at a time, and nationalizing the railroads. Williams was suggesting it was time to return to freer markets. After all, the rapid mobilization for World War I had demonstrated that an America that lived “free during peace times from the burdens of war” could vanquish “the most efficient and well-prepared military force that the world ever dreamed of.”

The next president, Warren Harding, opted for lifting those “burdens of war”—lowering taxes, cutting federal spending. Harding was also determined to make America more of an innovator’s play space. For treasury secretary, he chose a business icon and devoted student of innovation: Andrew Mellon. Before his time in government, Mellon had come up with a novel concept: the “research factory,” as Time magazine described it. Rather than simply go where pure science took them, professors at the “factory,” the Mellon Institute in Pittsburgh, conducted what we now know as applied research. Companies that needed an invention—whether a new drug for tuberculosis or a smoke-abatement tool—could contract with the institute to come up with the missing product. Often, the inventors under contract failed; but often enough, they satisfied the counterparty. By 1937, the research factory would yield 669 patents.

To welcome innovators, Harding and Mellon quickly addressed the tax that most constrains new businesses: the capital gains tax. At the time, the tax code treated capital gains the same as income, which meant investors could pay up to 73 percent on, say, profit from the sale of a stock. In 1921, Congress, at the urging of Harding and Mellon, cut the capital gains tax to 12.5 percent.

When Harding passed away in 1923, his successor, Calvin Coolidge, vowed to continue Harding’s pro-innovator campaign. Coolidge and Mellon led lawmakers in driving tax rates down yet further, so that by 1926 the top marginal rate on income stood at 25 percent, low by world standards. Under Coolidge, the regulators at the Federal Trade Commission went quiet. So did the Justice Department, the source of antitrust forays by Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and Woodrow Wilson.

The result of the Harding-Mellon-Coolidge restraint was average real growth of greater than 4 percent. That growth brought—attention, Representative Thomas Massie—sufficient revenue to pay down a third of federal debt. Progressives complained that the Roaring Twenties were creating too many millionaires. The public didn’t much care. For wages rose, especially for skilled workers; joblessness stayed low; and consumer goods from autos to washing machines were now priced within the reach of even the working class. Productivity gains meant the standard workweek moved from six days to five. It’s hard to quibble when you’re given a gift called “Saturday.”

But it was the speed of innovation that matters for our story. The 1920s were years—like the 1990s—when an engineer with an idea had a reasonable hope he could bring it to market. A Danish immigrant named William Knudsen figured out how to make a muffler with simple pieces in two minutes. Soon enough, he was manufacturing it at Chevrolet.

Henry Ford reduced the time it took to assemble the chassis from twelve and a half hours to one and a half. Ford envisioned and made a cheap auto that could achieve speeds nearly one-third faster than his Model T. Within four years, Americans had bought nearly 5 million of the new vehicle, the Model A. The patent rate, a metric of economic hope, exploded.

FDR Wipes Out the Playground

When the Depression hit, President Franklin Roosevelt made a punitive classroom of the playground. Not only did FDR raise taxes, but he also pushed through the Wagner Act, a pro-union law so powerful that it forced employers to pay wages they could ill afford.

Roosevelt also planted a dunce cap on any number of corporate leaders, or spanked them publicly in hearings or court cases. Not always, but still too often, the president supported the Nye Committee—led by North Dakota’s progressive (and Republican) senator, Gerald Nye—which dragged CEOs into hearings to charge them with profiteering during World War I. Mellon, the venerable ex–treasury secretary, spent much of the decade in court on trumped-up charges of tax evasion.

Businesses and inventors responded as anyone would: by putting their heads on their desks going quiet—or walking out of the classroom. The patent rate dropped. Net domestic investment by private companies, another measure of business hope, actually went negative, unusual for the American economy.

Still, rough as the New Deal was, it failed to destroy the great bank of knowledge and hope built up during the playful past. As Germany armed, and especially after France fell, FDR found himself more concerned with foreign wars than with playing economic schoolmaster. The White House dropped the legislation and lawsuits that terrified businesses. Suddenly, the dunces found themselves receiving invitations from Washington to talk contracts.

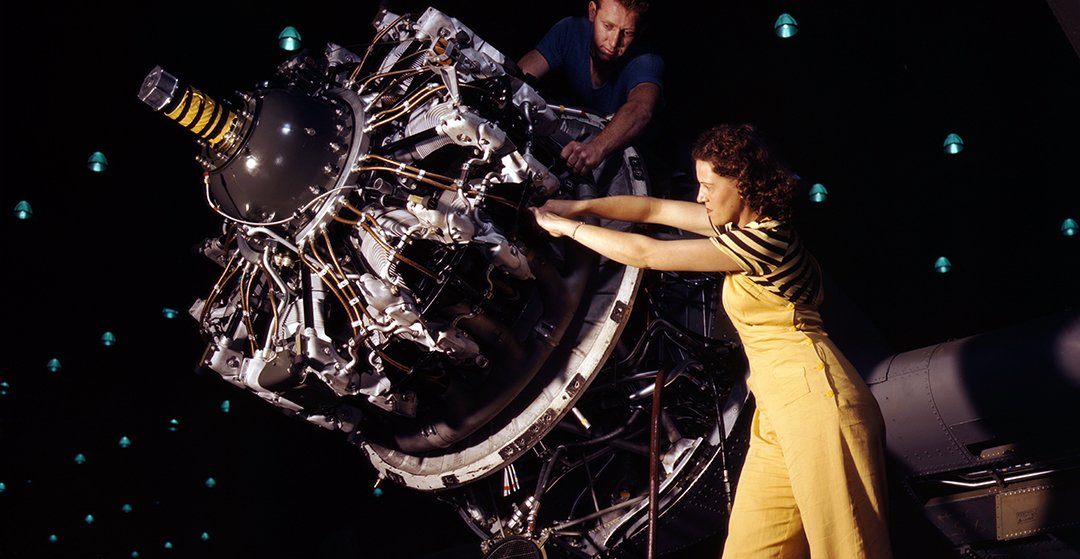

As Arthur Herman reports in his thorough Freedom’s Forge, FDR picked a legendary innovator as his point man for the war-mobilization effort: Knudsen of General Motors. Knudsen’s boss at GM, Alfred Sloan, warned him against taking the assignment: “They’ll make a monkey out of you down there.” Nonetheless, Knudsen, to his credit, joined up. So did that old isolationist Ford, who permitted his assembly lines to produce tanks and B-24 bombers. “Leaders of industry and labor have responded to our summons,” said FDR in 1941.

The dynamic operated just as Senator Williams of Mississippi had predicted a generation earlier. As Herman notes, the American military commenced this period so underprepared that it at first used Good Humor ice-cream trucks to stand in for decoy tanks in exercises. But thanks to Knudsen et al., America morphed into an unstoppable war engine practically overnight. Many technological surprises contributed to the eventual Allied victory: the code-breaking ability of mathematicians at Bletchley, the atom bomb, and radar.

That last surprise technology won our Navy the Battle of Midway. The Japanese might have beat us on radar, but Japan’s authorities and economy, both all fortress, showed scant interest in the Japanese professor who did the best work on antennae for long-wave airborne searches, Hidetsugu Yagi. The Japanese military woke up only when they captured a British searchlight-control apparatus in Singapore and discovered its antenna was a “Yagi.”

Keys to Cold War Victory

The power of policy that permits play also shows up in a more recent conflict, the Cold War. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the economic consensus held that the Soviet Union would outgrow the United States. In fact, the Cold War was one of those waiting-game wars. Soviet Russia wasn’t the powerhouse it seemed. The Kremlin relentlessly puffed up its data, a reality that only slowly dawned on the academic establishment here. Meanwhile, whether or not they grasped all the effects, American policymakers were taking steps that restored the old playground.

The first was the 1978 Steiger Amendment, a dramatic cut to the capital gains rate. Overnight the Steiger Amendment gave life to a new industry that served fledgling companies rather than already established firms: venture capital. The Labor Department changed its rules to allow pension funds to invest in the venture capital field.

Senators Birch Bayh and Bob Dole teamed up to see through a law that allowed universities to keep more of the intellectual property from their innovations. Venture capital exploded, with, over a decade, a sevenfold increase in cash investment. Among the results that eventually emerged—there’s always a lag—was the modern cellphone.

Soon enough came Ronald Reagan’s tax cuts, at which equity markets commenced their Long March upward. As Judy Shelton has noted, the Soviet Union spent many years losing the Cold War. But Mikhail Gorbachev gave up when he did because he ran out of money.

The Power of Innovation

The case for broad laws that inspire innovation is harder to make than one for specific projects. That case becomes yet more difficult as we confront budget deficits and entitlement commitments.

Still, the takeaways are clear. Subsidies for old weapons, the Golden Dome, and other carefully crafted programs will perhaps prove useful in the next war. What may matter more are the corporate tax cuts of President Trump’s 2017 law. Sustaining lower tax rates, as the new tax law does, will also help. A deep cut in the capital gains tax rate could do yet more—politically impossible as such a proposal may sound. So would stronger intellectual property laws and less regulation. For the technological surprise of the next conflict, or the conflict after that, will likely come from someone we don’t yet know.

Amity Shlaes chairs the Coolidge Foundation, is the author of Great Society, and is a fellow of National Review Institute. A version of this article first appeared in National Review’s “Capital Matters.”