The 3 Keys to Reclaiming the American Dream

By Ian Rowe

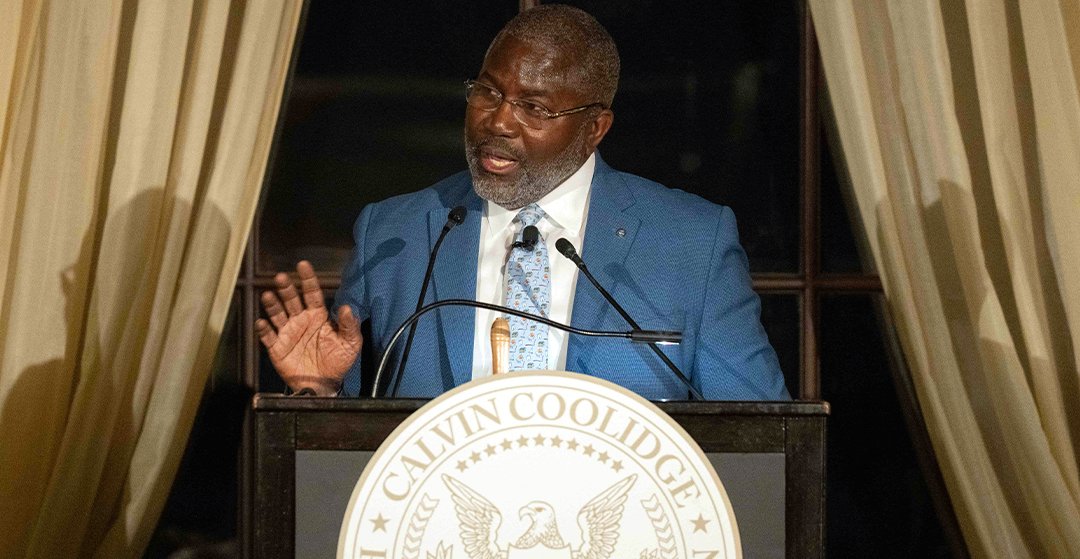

This article is adapted from Ian Rowe’s keynote address to the Coolidge Foundation’s 2025 Winter Gala.

I think I have become an honorary member of the Calvin Coolidge family, as I have now been to the president’s birthplace in Plymouth Notch, Vermont, three times to speak to the Coolidge Senators. And this past summer we had the incredible honor to watch an inspiring naturalization ceremony.

The proceeding was a testament to the legacy of Calvin Coolidge and his strong belief that we must cultivate within young Americans and new Americans a devotion to the principles of individual liberty, our common humanity, and a love for and loyalty to America that builds a spirit of self-reliance over excessive government assistance.

At the Notch, twenty-four immigrants from fourteen countries, including Bhutan, Vietnam, Iceland, Congo-Brazzaville, Congo-Kinshasa, Somalia, Germany, Canada, and Jamaica, became U.S. citizens. It was quite moving to listen to newly minted Americans recite the Oath of Allegiance, to “entirely renounce and abjure all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince, potentate, state, or sovereignty” and instead commit to the responsibilities of U.S. citizenship.

During the ceremony, the Coolidge Senators declaimed from President Coolidge’s 1925 speech “Toleration and Liberalism.” In that address, Coolidge spoke of the importance of finding common ground among diverse people from different backgrounds to create a unified America. The president offered these powerful words: “If we are to create on this continent a free Republic and an enlightened civilization that will be capable of reflecting the true greatness and glory of mankind, it will be necessary to regard these differences as accidental and unessential. We shall have to look beyond the outward manifestations of race and creed. Divine Providence has not bestowed upon any race a monopoly of patriotism and character.”

The naturalization ceremony reminded me of my own parents, Vincent and Eula Rowe, who had emigrated to England from Jamaica and ultimately came to the United States in 1968. That was a tumultuous time in our nation’s history, particularly around issues of race. But my parents weren’t running away from Jamaica or England; they were running to the United States in search of the American Dream. They believed a better life lay ahead for them and their two sons.

Yet we gather today amidst evidence that young Americans increasingly see the dream slipping out of reach. A recent UCLA study found that although 86 percent of fourteen- to twenty-seven-year-olds still find the American Dream desirable, 60 percent said it would be difficult for them personally to achieve it.

But underlying the concern about the attainability of the American Dream is seemingly a loss of reverence for America itself. The Atlantic published an article citing data that suggest most young people in the United States no longer believe that their country is anything special. In the early 1980s, nearly 70 percent of high school seniors agreed that “despite its many faults, [America’s] system of doing things is still the best in the world.” By 2022, that number had fallen to 27 percent.

President Coolidge would be dismayed by this decline in the belief in American exceptionalism. As a champion of free enterprise, he would be equally alarmed that the rising generation today seems increasingly skeptical of free-market capitalism to generate prosperity and more willing to embrace socialism for the government to provide basic needs.

In November, a front-page New York Times story highlighted the juxtaposition: “Tesla shareholders on Thursday approved a plan that could make Elon Musk the world’s first trillionaire, two days after New Yorkers elected a tax-the-rich candidate as their next mayor. These discrete moments offered strikingly different lessons about America and who deserves how much of its wealth.”

In his speech at the Tesla shareholder meeting, Elon Musk said that AI and his Optimus robots will increase the global economy by a factor of ten, maybe one hundred. He called his vision “sustainable abundance.” Meanwhile, Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani said in his victory speech, “We will prove that there is no problem too large for government to solve and no concern too small for it to care about.” In New York City, according to exit polls, 75 percent of young voters (ages eighteen to twenty-nine) voted for Mamdani, with this overwhelming support propelling him to his historic victory.

Which direction—sustainable abundance or government reliance—will we move in as a society? The answer will rely heavily on what young people understand are the factors that drive the American Dream.

As Coolidge wrote in 1930, “If we are to have any improvement, if public office is to be any more mindful of public welfare, if our national life is to be any purer, if our standards are to be any higher, it will be because the youth of the country make them so.”

So at a time when belief in the American Dream among young people seems to be in free fall, the moral imperative for the work of the Coolidge Foundation is even more urgent. We have the responsibility to offer the optimistic view and truth that the American Dream is real and it persists, even while acknowledging that it is not always fairly or evenly distributed. We just have to let young people know how they can live the dream and break the cycle of disadvantage.

Many Lands of Opportunity

In 2014, Harvard economist Raj Chetty and his team of researchers conducted a study entitled “Where Is the Land of Opportunity?” They researched the income records of more than forty million children and their parents. Their core sample, which is the largest sample ever done, consisted of all children in the United States born between 1980 and 1982. This cohort’s income was measured in 2011–12, when the subjects were approximately thirty years old. Chetty and his team identified localities where children from families in the lowest 20 percent of income at birth were most likely to have incomes in the top 20 percent as adults, thirty years later.

If you go to OpportunityAtlas.org, you will see the resulting map—the geography of upward mobility.

The first thing you will notice is the substantial variation in intergenerational mobility across the United States. While we are all governed by the same national policies, the variation suggests that what matters most in terms of upward mobility is what happens locally. This finding hews to one of Coolidge’s core beliefs: that the federal government should play as minimal a role as possible in the everyday affairs of Americans, and that instead we should rely more on small-town values and the thrift of local leaders to drive America forward.

The Chetty study describes the United States as a “collection of societies, some of which are ‘lands of opportunity’ with high rates of mobility across generations, and others that experience persistent inequality, places in which few children escape poverty.”

The question is: Why? What is it that ties these lands of opportunity together?

If we can understand the most important characteristics of areas where intergenerational mobility is high, then we can be in a better position to replicate that mobility in other communities.

Three Crucial Factors

I will home in on three characteristics that the study shows correlate most with the lands of opportunity.

First, “the strongest predictors of upward mobility are measures of family structure such as the concentration of married two-parent households in the area.”

Second, “high upward mobility areas tend to have higher fractions of religious individuals and greater participation in local civic organizations.”

Third, “proxies for the quality of the K-12 school system are also correlated with upward mobility.”

It is no coincidence that these three factors—high rates of family stability exemplified by married, two-parent households; concentrations of religious individuals; and access to high-quality K-12 education—are strongly correlated to upward mobility at the neighborhood level.

For more than thirty years, I have had the honor of working with kids from every imaginable background—rich kids, poor kids; black, white, Hispanic, Asian kids; kids from intact families, kids from completely unstable families; kids in foster care; homeless kids. I have seen kids grow up in challenging situations—domestic violence, poverty—who succumb to those conditions and unfortunately re-create them as they enter young adulthood, perpetuating the cycle of degradation. It’s heartbreaking.

But I have also seen kids who grow up under those same exact conditions but make different sets of decisions that put them on a trajectory to break the cycle of disadvantage. The question is: What makes the difference?

That has been the animating question of my life.

My observation is that students who have been able to break the cycle of disadvantage typically have a sense of personal agency—a belief that they can lead a self-determined life of meaning and purpose.

Now, having a sense of agency doesn’t come from nowhere. Agency is individually practiced yet socially empowered. In my experience, young people who exercise agency have usually embraced the four pillars of human flourishing, what I call FREE: Family, Religion, Education, and Entrepreneurship. These are the institutions we must revitalize to strengthen our country.

Coolidge was prescient in 1930 when he wrote, “The moral power of the nation rests on the home, the schoolhouse, and the place of worship.” His insight maps completely onto the Chetty study.

The reason I run schools is that I want our students to know they can do hard things. Even in the face of inevitable challenges, they can lead virtuous, self-determined lives with integrity and agency. This is what my parents taught me.

Let me give you an example from our high school in the Bronx, Vertex Partnership Academies. Vertex is organized around the four cardinal virtues of Courage, Justice, Temperance, and Wisdom. These are called cardinal virtues (from the Latin “cardo,” which means “hinge”) because they are the root virtues on which all other standards of moral excellence depend. So gratitude, determination, perseverance, optimism, hope—all these character-based strengths emanate from the four cardinal virtues.

One way we get Vertex students to internalize the cardinal virtues is by requiring them to memorize an “I statement” associated with each one. Here are the statements:

Courage: I reject victimhood and boldly persevere, even in times of uncertainty and struggle.

Justice: I uphold our common humanity and honor the inherent dignity of each individual.

Temperance: I lead my life with self-discipline because I am responsible for my learning and behavior.

Wisdom: I make sound judgments based on knowledge of objective, universal truth.

The idea is that, by memorizing and repeating these statements, students first grasp the cardinal virtues in their heads, intellectually. But the ultimate goal is that they grasp the virtues in their hearts, so that these virtues inform their everyday decisions about their lives. When our students say these words out loud, in unison, it goes beyond an individual statement. It becomes a collective commitment about how we will live and thrive together as a community.

The Need for Sound Economics

Beyond cultivating virtue, our school makes a deliberate effort to cultivate true financial literacy. This effort addresses the growing ignorance and skepticism of markets I discussed earlier, along with young people’s willingness to embrace socialism. For as President Coolidge warned, “Unless there be some teaching of sound economics in the schools, the voter and taxpayer are in danger of accepting vague theories which lead only to social discontent and public disaster.”

In Vertex’s required economics course, there is a unit entitled Facts, Fallacies, and Freedom: Thomas Sowell and the Pursuit of Truth. High school students must read from Sowell’s Basic Economics. At the end of the unit, students will be able to do four things:

Think like social scientists, using evidence, logic, and data to evaluate claims.

Recognize myths and fallacies that distort understanding of inequality and achievement.

Apply economic and sociological reasoning to real-world problems of opportunity and development.

Communicate empirically supported arguments about human potential.

I should mention that teachers’ unions sued to try to block Vertex from opening. This is in a district in which only 7 percent of kids graduate from high school ready for college. Can you imagine that? Vertex is bringing a world-class, virtues-based education to an area desperately in need of educational alternatives, and that’s the fight the teachers’ unions chose to pursue. But we won that fight.

The Power of Self-Renewal

Let me close by quoting a line attributed to Alexis de Tocqueville: “The greatness of America lies not in being more enlightened than any other nation, but rather in her ability to repair her faults.”

I find this statement compelling because it suggests that our country, through its founding documents—the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, the Bill of Rights—has within itself the tools of self-renewal, the power of self-betterment. America has a story still to be told as we strive to become a more perfect union.

At Vertex, one of our rituals is that our students recite the Preamble to the Constitution each morning to remind them that “we the people”—we are the people to shape the future and secure the blessings of liberty. The goal is to instill within our students the knowledge that, like our country, they also have the tools of self-betterment and self-renewal within themselves.

Young people should know that they live in a remarkable country that is not hostile to their dreams but in fact can help make those dreams come true if they live with virtue, as architects of their own lives.

Ian Rowe is the CEO and cofounder of Vertex Partnership Academies, a network of character-based International Baccalaureate high schools inaugurated in the Bronx in 2022. He is also a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. This article is adapted from his keynote address at the Coolidge Foundation’s 2025 Winter Gala, held December 9 at the Union League Club in New York City.