Merchant of the Revolution

By Amity Shlaes

This review is adapted from Amity Shlaes’s regular column “The Forgotten Book,” which she pens for “Capital Matters” as a fellow of National Review Institute.

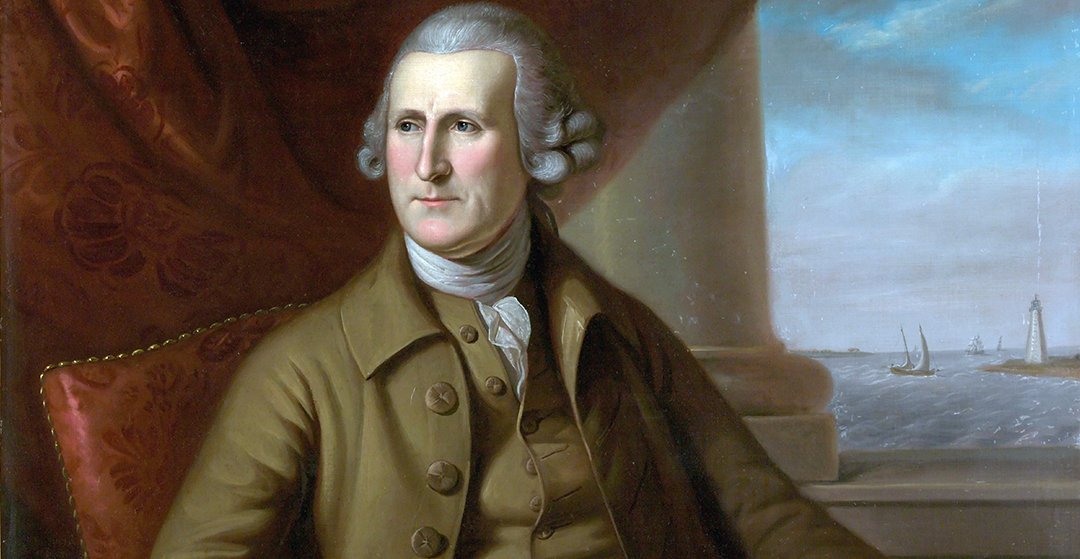

The Banker Who Made America: Thomas Willing and the Rise of the American Financial Aristocracy, 1731–1821, by Richard Vague (Polity, $35)

There are two kinds of people in the world: people who break things, and people who put the pieces back together.

Into the latter category falls banker Thomas Willing, among the delegates to the Continental Congress at Philadelphia in 1776. When the “committee of the whole” voted on American independence, Willing voted no—twice. The fact ensured that we find no Willing–Hamilton duet in the musical Hamilton. Thomas Paine gets hero status in the celebration of the 250th anniversary of our independence.

But not Thomas Willing.

All the more welcome then is The Banker Who Made America, by Richard Vague. Vague claims that Willing was “the most powerful figure in early American history that you’ve never heard of.”

The author’s scholarship validates his claim. Son of a Philadelphia mayor and founder of the University of Pennsylvania, Willing himself served as mayor and then as a merchant banker so successful that John Adams feared that Willing and family would get “possession of all Pennsylvania.” Despite those “no” votes, Willing subsequently funded or had a hand in funding the survival and growth of the new republic. Willing served as president of the Bank of North America, chartered expressly to finance the revolutionaries. Later, the Founders tapped Willing as the first president of the First Bank of the United States, a proto-Fed that would serve as “the great regulating wheel of all Commercial Banks in the United States,” as Willing put it.

Vague happens to be one of the financial cognoscenti of our own age, which enables him to capture the reasons for the Willing family’s trajectory. Willing’s father, Charles, established a family in Pennsylvania at a time when banking was “a pathless wilderness,” as Willing himself later noted. These banking frontiersmen had customs that today look grand. At the age of eight, Thomas was shipped to England to study. Another Willing laid out the grid for a settlement that they first called Willingtown. But that name was soon enough traded for Wilmington (Delaware), after the earl of Wilmington. The Willings were merchants, not royalty.

Inheriting the family shipping business on his father’s death, the young man talked modestly—“I propose to continue in business”—and moved boldly, adding a fourth ship to the family’s fleet. Within three decades, the Willings’ business would be fifty times the size it had been at Charles’s death. A “capacity for adaptation, compromise, moderation, and goodwill which prevailed over extremes” goes a good way to explaining that success.

As Vague notes, Willing grasped principles of business that seem mundane to us but were rarely applied, or even recognized, in his day: diversification to reduce risk, and the two magics: the magic of the actuarial pool and the magic of compounding. Later, Willing invested in a then-new business, life insurance. Perhaps excited at the prospect not merely of profits but also of protecting widows, Willing penned a pamphlet: “An Address to the Citizens of Pennsylvania Upon the Subject of a Life Insurance Company.”

Rescue Artist

Vague offers a reason for Willing’s mysterious 1776 “no” votes: class war. On the one side stood Scots-Irish Presbyterian farmers, artisans, and laborers, whom Vague casts, in archaic and vaguely offensive terminology, as “middling and lower sorts.” “Middling” and “lower” demanded American independence. On the other side, clustered on Third Street and Chestnut, stood more prosperous Quakers and Anglicans, who saw little use in revolution.

In 1776, the local rebels staged a coup in Pennsylvania. They held a convention that dissolved the state government and wrote a new constitution as radical as anything Andrew Jackson would later dream up: unicameral, with an elected judiciary and lame executive. The same rebel group gained control of Pennsylvania’s delegation to the Second Continental Congress. Willing refused to vote with the rebels because, he claimed, he did not want to recognize their status.

Vague rates this explanation “at least somewhat disingenuous.” More plausible is that Willing was torn. The Declaration forced war. Like Alexander Hamilton, who at one point mooted a “limited monarchy” for America, Willing saw much good in Britain. He said he wished “well to both countries.”

In any case, he took the risk of funding the revolution, once under way. He wanted to support his country. That there was profit in the venture did not hurt, either. His ships, or his partners’, received letters of marque, authorizing them to attack British merchant ships and split the booty with Congress. Within short order, the British were down 350 ships. When the bank that would be key to the war’s finances finally opened in January 1782 (in a building that belonged to Willing’s brother-in-law), Washington came to pay his respects.

Vague chronicles further Willing rescues. Washington chose to crush the Whiskey Rebellion with the costly option, overwhelming force—and turned to Willing for a loan. Jefferson and Madison convinced Congress to indulge in the extravagance of the Louisiana Purchase—and asked Willing to organize payment.

A Class-War Morality Play

In a way, this book feels like two books. Beyond biography, Vague seems determined to render not just Pennsylvania’s constitutional conflict of 1776 and the Whiskey Rebellion but the entire story of Willing and early America as a Hillbilly Elegy prequel. Vague tags Willing as part of the “merchant elite” or, simply, the “elite,” a term that appears dozens of times. For less wealthy Scots-Irish and, more generally, lower-earning Americans, Vague repeatedly uses that pejorative, “middling and lower sorts.” He writes, “Factions fought a virulent class war within America that has raged episodically and in different guises ever since.” His subtitle suggests permanent class war: “The Rise of the American Financial Aristocracy.”

“Aristocracy” is too simple. Northern bankers were immigrants, often upstarts—some rich, some less so. Vague does not explain how that bastard from the Caribbean, Hamilton, could be an aristocrat. Nor does he explain how Jefferson of Monticello and Madison of Montpelier, the closest the colonies had to aristocrats, opposed that aristocratic institution, the First Bank of the United States. Vague even offers Willing’s story as a kind of morality play to warn Goldman Sachs globalists today.

The duration and seriousness of class war is contestable. Willing deserves more than to be used in service to such an argument. A less cartoonish picture of Willing and his era lies in Robert E. Wright and David J. Cowen’s Financial Founding Fathers. These authors’ Willing was local and global—but not particularly national. He and his friends built their own republic of merchants. More Burke than Paine, they brought prosperity even to the “lower sort.” Rich men, after all, do not need life insurance.

Vague’s emphasis, however, does not delete his achievement: the full-length biography of Willing that was missing from our shelves. In tumultuous times, what better rule to observe than Willing’s? Serve where you can, and “continue in business.”

Amity Shlaes chairs the Coolidge Foundation, is the author of Great Society, and is a fellow of National Review Institute. She is at work on a history of the Gilded Age.

The Coolidge Review has republished this article courtesy of National Review. The original version of the article appeared in National Review’s “Capital Matters.”