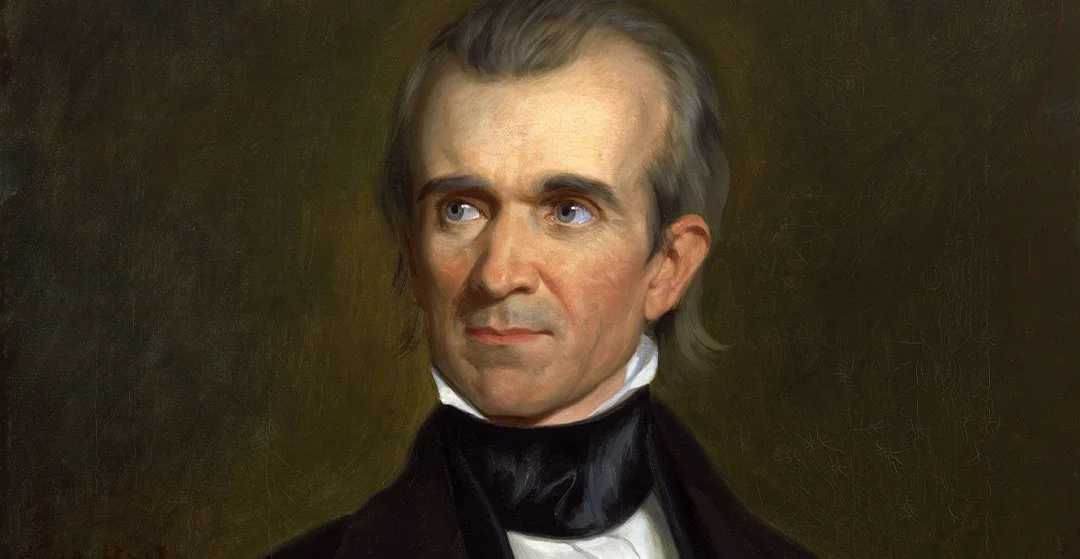

James K. Polk and the 5,106 Votes That Changed America

President James K. Polk was underestimated is his own time and has been mischaracterized since

By Walter R. Borneman

This article appears in the Winter 2026 issue of the Coolidge Review. Request a free copy of a future print issue.

“Who is James K. Polk?” the Nashville Republican Banner asked in a headline after news of Polk’s nomination as the 1844 Democratic Party standard-bearer reached the Tennessee capital. The question was meant to be derisive, and it struck so shrill a chord that the Whigs adopted it as their national campaign taunt.

The truth is that Polk’s political opponents knew very well who James K. Polk was—and why they should fear him. Yet almost two centuries later, despite solid standing in modern presidential polls and a portrait that currently graces the Oval Office, Polk’s legacy is entwined in mischaracterizations.

The Myth of the Dark Horse

Many will tell you that Polk was a dark horse. No, he was not.

Born in North Carolina in 1795, Polk aspired to the presidency at least from his first election to the Tennessee House of Representatives at the age of twenty-eight. He always had what every budding politician craves: the unqualified support of the era’s greatest hero. Although some vilified Andrew Jackson, Old Hickory was a political force that could not be denied. With Jackson’s encouragement, Polk entered politics and then married Sarah Childress, whom Andrew and Rachel Jackson treated as a daughter.

Prior to his nomination, Polk had served seven terms in Congress, including two as Speaker of the House; he had been governor of Tennessee; and he had tried to unseat the sitting vice president to become President Martin Van Buren’s running mate in 1840. To be sure, there were defeats along the way. Polk lost his first try for the Speakership and two gubernatorial campaigns in Tennessee, a state as bitterly divided as any between Jackson’s Democrats and emerging Whig forces.

But Polk never lost sight of the prize. Even in defeat, he continued to correspond with Democratic leaders across the country. His presidential nomination in 1844 at a convention divided over the annexation of Texas may well have been—as one of his most ardent supporters advised—four years ahead of schedule. After all, former president Van Buren, who had lost his reelection campaign in 1840, again sought the nomination in 1844. But Polk was not a dark horse suddenly surging from the back of the field. He was in the arena and one of the most astute and well-connected politicians of his day.

54°40 ′ or…Compromise?

History’s shorthand has long associated the battle cry “54°40 ′ or Fight!” with Polk’s election campaign. In reality, it wasn’t until much later that the phrase emerged as a slogan for acquiring all of the Oregon Territory south of Russian Alaska. Polk was too shrewd a politician to be boxed in by so blunt a threat.

Britain and the United States had jointly occupied this vast territory since 1818. During the 1844 campaign, the Democratic platform resolved that America’s “title to the whole of the Territory of Oregon is clear and unquestionable.” After assuming office, however, Polk offered the British a compromise: to divide the Oregon Territory at the forty-ninth parallel. The British rejected the proposal, at which point Polk withdrew it.

In December 1845, in his first annual message to Congress, Polk reiterated America’s “title to the whole Oregon Territory.” The president urged Congress to give Britain the one-year notice required to terminate the joint occupation agreement over Oregon.

In the ensuing debate over whether to issue the resolution, some senators proved too transparent for Polk’s taste in suggesting they might be satisfied with a territorial compromise. They charged the “all of Oregon” faction with promoting “54°40 ′ at all hazards” and risking “54°40 ′, war or no war.” Then, on March 11, 1846, one year into Polk’s presidency, Senator Reverdy Johnson of Maryland, a Whig, referred to “hotspurs of the Senate” who “were all for 54, 40 or fight.”

There it was.

Almost overnight, “54°40 ′ or Fight!” was painted on storefronts and chalked on sidewalks throughout Washington. Thanks to a nineteenth-century media blitz, the most widely remembered slogan of Polk’s career swept the country—in 1846, not 1844.

But where did that leave Polk in acquiring any of Oregon? Having finally passed a resolution giving Britain the one-year termination notice, the Senate draped it with an olive branch, hoping that “an amicable settlement of all their differences” might be reached.

Recognizing the obvious divisions in the American Congress, Great Britain proposed to split the Oregon country at the forty-ninth parallel—the current U.S.–Canadian border—with a small jog southward to encompass Vancouver Island.

By the time Great Britain’s offer reached Washington, Polk faced a certain war with Mexico over America’s annexation of Texas. Polk chose to submit the Oregon treaty to the Senate for its “advice” before seeking its “consent.” The moderates prevailed. The Senate advised ratification and subsequently gave its consent, 41 to 14. The battle cry to fight for all of Oregon became the political reality of “54°40 ′ or Compromise.”

For Polk, it was a political win-win. He had maintained his position for “the whole Oregon Territory,” but by involving the Senate upfront, he placed the fallout from any compromise on that body. He became the man who won Oregon south of the forty-ninth parallel without firing a shot, and the “hotspurs of the Senate” took the criticism for failing to fight for the rest of the territory.

Misunderstood Expansionist

The election of 1844 proved in retrospect a national referendum on the geographic extent of the country. Whig nominee Henry Clay cared little how Oregon was divided with Great Britain, and he sought to avoid war with Mexico over Texas. Certainly, Clay had no designs on California or the remainder of the Southwest. Why did Polk?

Many ascribe Polk’s expansionism to an overriding goal to extend slavery as an institution and bring about the admission of more slave states. Polk was indeed a slaveholder, although he went to some lengths to keep purchases for his Mississippi plantation private. He called the Wilmot Proviso, an attempt to ban slavery in territories acquired from Mexico, “mischievous and foolish.” When Congress passed legislation organizing a territorial government for Oregon that recognized antislavery laws already in place there, Polk made clear to Congress that he signed the bill only because Oregon lay well north of the 1820 Missouri Compromise line.

But Polk also intended his message on Oregon to be a call for national unity, and he included a lengthy quotation from Washington’s Farewell Address warning against “geographical discriminations.” Polk sought balance to accord the South some measure of compromise that he deemed essential to preserving the union. To Polk, the extension of slavery was “a mere political question” on which ambitious politicians hoped to promote their own prospects “even at the hazard of disturbing the harmony if not dissolving the Union itself.”

And that was Polk’s true intent—to expand the Union and preserve it in the unionist mold of another slaveholder, his mentor Andrew Jackson. “Manifest Destiny,” another phrase coined after the 1844 election but long associated with it, was at the core of both men. Polk was fixated on continental expansion, not the extension of slavery. There is no better evidence than the fact that after he had won California and America extended sea to sea, he reached still further. His administration negotiated an annexation treaty for Hawaii that was never signed, offered Russia five million dollars for Alaska, and attempted to entice Spain to sell Cuba.

A Mere 5,106 Votes

The irony of Polk’s legacy of continental expansion is that the changes hinged on a margin of 5,106 votes in the 1844 election. That was the amount by which Polk defeated Clay in New York State, allowing him to capture its thirty-six electoral votes and win the presidency. This margin might have evaporated but for the presence of a third-party candidate, James G. Birney of the abolitionist Liberty Party, who polled 15,812 votes in New York. While it is uncertain how many Birney votes might have gone to Clay, one ardent Clay supporter in Illinois thought the result obvious: “If the Whig abolitionists of New York had voted with us,” bemoaned an aspiring politician named Abraham Lincoln, “Mr. Clay would now be president.”

Had that happened, America would have likely paused—for four years, a decade, a generation, who knows?—its westward expansion. That it did not and instead almost doubled in size in a few years was due to James K. Polk’s assertive leadership in pursuit of his vision for America.

Experienced politician, shrewd diplomat, and defender of the Union—that is the answer to the question “Who is James K. Polk?”

Walter R. Borneman is the author of Polk: The Man Who Transformed the Presidency and America. He is an independent historian whose books include American Spring, 1812, The Admirals, and MacArthur at War.

This article appears in the Winter 2026 issue of the Coolidge Review. Request a free copy of a future print issue.