1929: Sorkin Rounds Up the Usual Suspects

By Amity Shlaes

This essay is adapted from Amity Shlaes’s regular column “The Forgotten Book,” which she pens for “Capital Matters” as a fellow of National Review Institute.

Back in 1999, William F. Buckley Jr. interviewed the economist John Kenneth Galbraith on Firing Line. The gents’ topic was historic figures. Around twenty-four minutes in, Buckley got to President Franklin Roosevelt. Galbraith, then ninety, turned nostalgic.

“Of my generation, there was no figure like Franklin Delano Roosevelt. And I still wake up in the morning and say, ‘Well, Galbraith, you’re still a New Dealer.’ ”

Certainly. But do the rest of us have to be?

Apparently, yes. For “We are all New Dealers now” is likewise a conclusion of Andrew Ross Sorkin’s 1929, an artful reprise of Galbraith’s book on the same topic, The Great Crash, 1929.

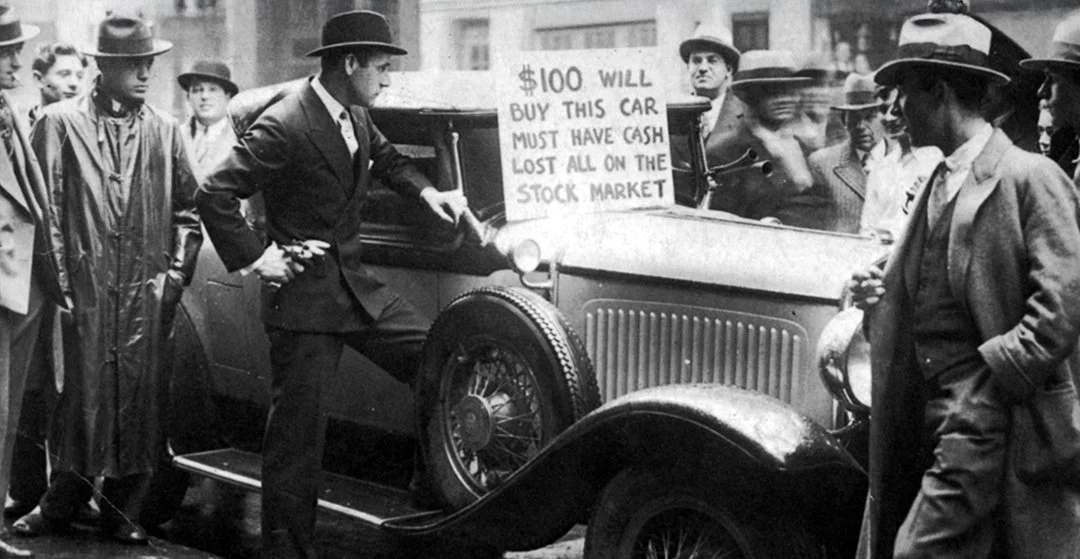

In that 1955 book, Galbraith argued that unregulated speculation, exacerbated by lazy statesmen and the greed of the rich, caused the Great Crash. Galbraith’s choice of a narrow time frame—one short year, 1929—helped him to capture the drama of the crash.

According to Galbraith, quoted approvingly as “seminal” by Sorkin, the worst day of the Great Crash—Tuesday, October 29—was “the most devastating day in the history of the New York stock market,” and “may have been the most devastating day in the history of markets.”

The stunning story of the market’s plummet, however, also emboldened Galbraith to moot, without seeing any necessity of proving, a second thesis relating to years outside the scope of his title: that the 1930s policy applied by President Roosevelt, the New Deal, somehow made matters better, or could have, had the crash not been so violent.

The 1929 frame likewise enabled Galbraith to establish villains of speculation, and hero rescuers such as President Roosevelt. Roosevelt rated the damage of the national “fever of speculation” as so devastating that, at his inauguration in 1933, he announced that his presidency would begin a new, post-speculation era.

“The money changers have fled from their high seats in the temple of our civilization,” the new president proclaimed. (Yes, FDR, talking like Tucker Carlson, actually said “money changers.”) “We may now restore that temple to the ancient truths.”

By titling his book 1929, not 1929–1940, Galbraith skated past the inconvenient truth of the 1930s record. The New Deal honored Roosevelt’s anti-market “ancient truths.” Fueled by its own rage against Wall Street and a wrongheaded notion that Main Street would return to prosperity if it took lessons from planning boards, the Roosevelt administration never allowed either to find its footing. The result was that one in ten Americans remained jobless for a full decade. That is a level that today looks worse than inconvenient; it looks incomprehensible.

Galbraith’s primary thesis, that speculation caused the crash, was questionable. The second thesis, that the crash rendered the Depression “Great,” was spectacularly wrong.

One can make like Buckley, smile indulgently at Galbraith as a man of his time, and move on. But Sorkin is publishing in 2025, after a number of market drops that have not been followed by a depression, including the October 19, 1987, “Black Monday” drop and the Covid drop on March 16, 2020—both statistically larger than the single-day drops of 1929.

The Myth of Inevitability

By his own claim, Sorkin devoted “eight years of reporting and thousands of hours of research” to producing 1929. One result is a compelling narrative offering a sympathetic portrait of Charles Edwin Mitchell, the often-reviled president of First National City Bank, the forerunner of Citibank.

In Sorkin’s telling, Mitchell, who dumped cash into the market to save his depositors, fellow National City owners, was something of a hero. After all, Mitchell risked his bank and personal assets when he waded into the market to prop it up, just as J. P. Morgan had, with more success, during the Panic of 1907. According to Sorkin, Mitchell, and some of the other players in 1929, did not do anything “appreciably worse than most individuals would have done in their positions and circumstances.”

True. What disappoints is that Sorkin chooses not to draw his own conclusions—i.e., revise the narrative of the period along with some of those who played a part in it. Instead, retracing Galbraith, he suggests inevitability: the crash, caused by bad actors, so “scarred” the country and broke citizens’ trust that we could not recover in the 1930s.

In preparing his analysis, Sorkin chose to overlook those who have fundamentally shifted our understanding of the causes of the Depression’s duration since Galbraith published: Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz (A Monetary History of the United States, 1963), Michael Bordo (The Defining Moment, 1998), David Kennedy (Freedom from Fear, 1999), and as-yet lesser known scholars who have brought a crucial public choice perspective to the New Deal (Benjamin Anderson, Economics and the Public Welfare, 1949, and Robert Wright, most recently in FDR’s Long New Deal, 2024). Instead of straightening out an important period of history, Sorkin irons in the old Galbraith errors.

It’s therefore not too small—it’s worthwhile, even—to review the chain of crumpled Galbraithian assumptions that inform Sorkin’s fallacy.

Morality Play, Not History

The trouble starts with Sorkin’s portrait of the Roaring Twenties. Sorkin, like Galbraith, posits that “a massive bifurcation” of society into rich and poor, “urban haves and rural have-nots,” represented one of several ominous “underlying imbalances” that led to the crash. The financial distance between the wealthiest and the poorest did widen in the 1920s. But lower earners saw “massive”—to use a Sorkin adjective—increases in their standard of living. The 1920s were the decade that gave us indoor plumbing, Ford’s Model A, and electrification. Sorkin supplies no evidence of how a dollar-wealth disparity caused either Crash or Depression. That’s because there isn’t much.

In the 1920s, according to Sorkin, “greed” was the problem. He treats the rise of consumer credit—GM’s decision to sell autos on credit, for example—as another imbalance leading to the crash. Citizens became overly confident in markets. In fact, however, the 1920s federal policy of lower taxes and less regulation was what gave citizens confidence, more in themselves and business than in the faraway New York trading floor. And for good reason. It was not the market crash but a shift away from such restrained policy in the 1930s that transformed a historic stock market crash into a historic economic siege.

Sorkin suggests that “by encouraging speculation and promising outsized returns to a new class of investors…the titans of Wall Street helped magnify the damage when the collapse finally came.” In reality, that “class” was too small to force a Depression. As historian David Kennedy and the U.S. Treasury have noted, only 3 million Americans owned stock in the late 1920s, or less than 3 percent of the population of 120 million or so. Main Street mattered far more than Wall Street in those days.

Sorkin lionizes Representative Henry B. Steagall, a Democrat from Alabama, for insisting on the establishment of deposit insurance, and suggests the imperative for that establishment by writing that “panicked depositors, desperate for cash, continued to descend on banks in waves.” When deposit insurance became law, “small-town America finally felt like it had won a battle with Wall Street.”

Yet that battle was perhaps the wrong one. As one of the nation’s premier banking scholars, Charles Calomiris, has noted, depositors actually lost only 2.7 percent of their deposits in the crunch years of 1930–1933.

The number of bank failures in the downturn was indeed stupendous: some nine thousand banks. Yet a good share of the banks that failed, Sorkin’s National City account notwithstanding, were small ones, not so different from the fictional Building & Loan that so narrowly dodged that fate in the film It’s a Wonderful Life. As Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz noted, the trouble was that these banks operated outside the Fed system and therefore had little access to capital when they struggled. It’s likely that national reform to include small, sometimes single-office “unit banks” in the same network as alpha Money Center banks would have strengthened the economy generally.

The Fed itself also worsened the dire shortage of money in the early Depression by failing to recognize the need for extra cash at certain points, though how much the Fed should have poured in and under what principles has been a topic of its own jumbled debate since Friedman and Schwartz published. The money matter is, in any case, more important than factors that Galbraith and Sorkin emphasize.

Nearly entirely ignored in both Galbraith and Sorkin are the forces that kept the economy down through the 1930s. Roosevelt exploited the drama of the downturn to mount a government takeover of the industrial economy via his National Recovery Administration, or NRA. The NRA established both price and wage controls so far-reaching that it “retarded” recovery, as the Brookings Institution, not exactly a right-wing outfit, concluded in a 1935 study. Later in the 1930s, as labor scholar Lee Ohanian has shown, further Roosevelt efforts to push up wages, most especially the outrageously pro-union Wagner Act, rendered re-employment too expensive for strapped employers. Hence, the enduring nature of joblessness.

By choosing to treat the 1930s as a form of extreme payback for extreme excess—“no generation exempt”—Sorkin stages morality play rather than history. He also helps set policymakers up for the kind of grand theatrical action they are inclined to take anyhow whenever markets turn down. In other words, another 1933- or 2008-style rescue: flooding the market with liquidity, and stringing up wrongdoers and even the better Wall Streeters, such as the Mitchells whom Sorkin seeks to rehab. The same subpar results are likely to follow.

When Government Plays God

Both Galbraith and Sorkin imply the imperative of an omnipotent rescuer: a spending, managing, and punishing government. Galbraith, after all, was the great popularizer of John Maynard Keynes. His son, James K. Galbraith, has carried on that tradition, as in a 2014 book, where he called for restoring “the understanding achieved by Keynes and [Hyman] Minsky, and under the New Deal, of unstable speculation and financial fraud.” That understanding, the younger Galbraith added regretfully, was later “effaced by the doctrine of efficient markets.”

But efficient-market was not the only theory that challenged the New Dealers’ analysis. Scholars of the Austrian and Public Choice schools have done us the service of documenting that government’s reflexive tendency to intervention can itself be as fraudulent as any bucket shop.

During the New Deal, and to a disconcerting extent, federal intervention served political ends more than the economic goal of reemployment. The result was that a depression became “the Depression.” As Benjamin Anderson, who lived through the 1930s as an economist at Chase, put it in his own history: “Preceding chapters have explained the Great Depression of 1930–1939 as due to the efforts of governments, and very especially of the Government of the United States, to play God.” When playing God failed, Anderson noted, our government had determined that “far from retiring from the role of God,” it “must play God yet more vigorously.”

Were 1929 a documentary produced by Michael Moore, its suggestions would not matter. We are accustomed to illogic in television. But 1929 presents itself as the researched book Sorkin wants it to be. It therefore claims the authority that such books can carry.

Sorkin quotes H. G. Wells, who called human history “a race between education and catastrophe.” Indeed, indeed. But for education to beat catastrophe, that education must be a little more thorough.

Amity Shlaes chairs the Coolidge Foundation, is the author of Great Society, and is a fellow of National Review Institute. She is at work on a history of the Gilded Age.

A version of this article first appeared in National Review’s “Capital Matters.”