Was Calvin Coolidge Native American?

President Calvin Coolidge wears the headdress that Sioux leaders presented to him on August 4, 1927

(Everett Collection/Alamy Stock Photo, colorized by BigWhiskeyArt.com)

By the Editors

This article appears in the Summer 2025 issue of the Coolidge Review. Request a free copy of a future print issue.

Calvin Coolidge believed he might have Native American ancestry. In his Autobiography, Coolidge wrote that relatives on his father’s side—namely, his great-grandmother Sarah Thompson Coolidge and her family—“showed a marked trace of Indian blood.”

Coolidge may have thought he had Native American heritage on his mother’s side as well. Coolidge Foundation friend and former colleague Tracy Messer has spent significant time reviewing the Coolidge family papers, which are housed at the Vermont Historical Society. Messer discovered notes in the family papers showing that someone—possibly President Coolidge, his father, or his mother—actively researched the family tree.

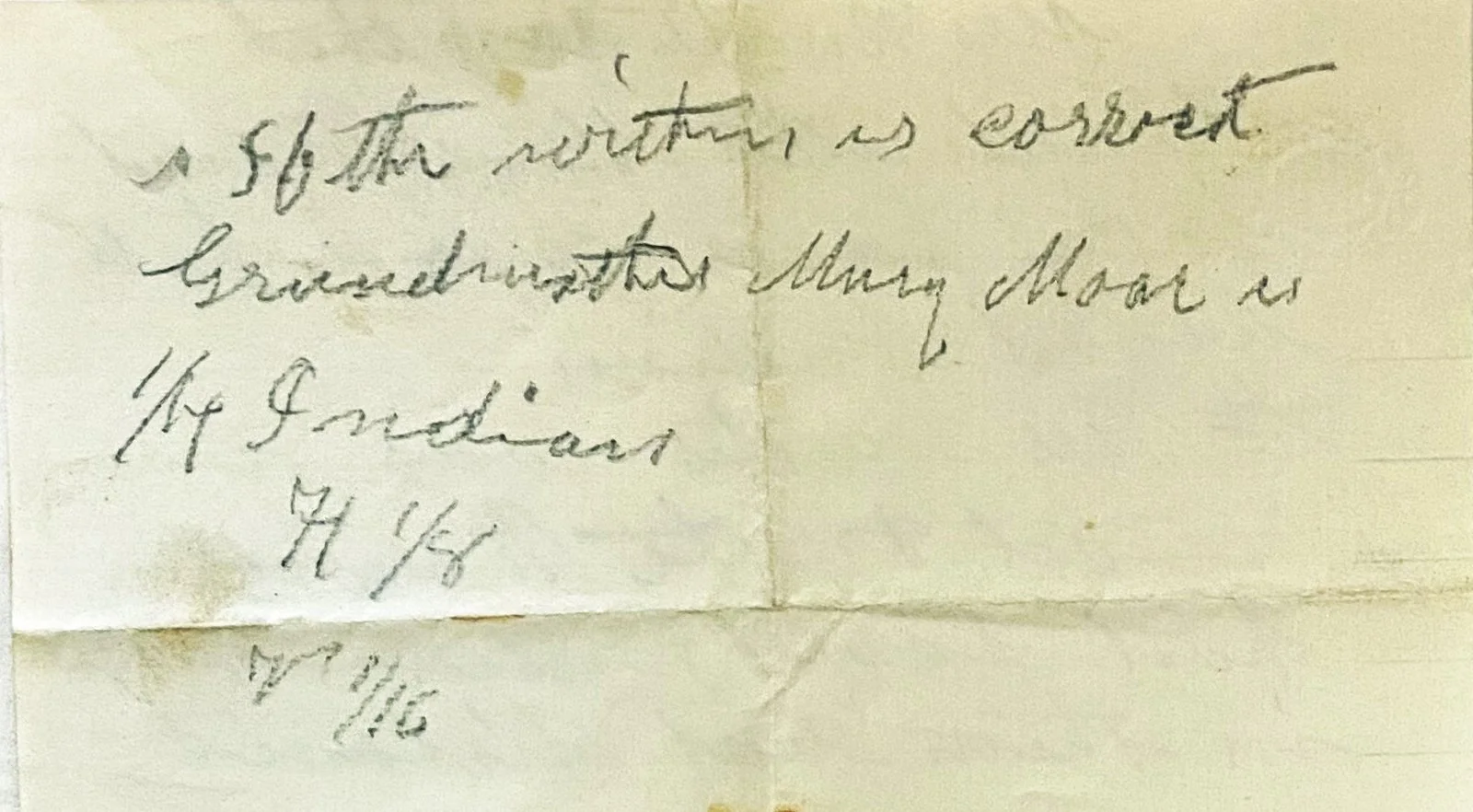

One handwritten note suggests that a family member found evidence of Native American ancestry. The note reads:

If the within is correct Grandmother Mary Moor is 1/4 Indian

H 1/8

V 1/16

The documents to which the note refers (“the within”) are not known, but “Grandmother Mary Moor” would be Mary (Davis) Moor (1787–1870). “H” probably stands for her son Hiram Dunlap Moor (1812–1888). Hiram Moor was the father of Victoria Josephine (Moor) Coolidge (1846–1885)—the “V” mentioned. Victoria was President Coolidge’s mother.

The note Tracy Messer discovered in the Coolidge family papers: “If the within is correct Grandmother Mary Moor is 1/4 Indian, H 1/8, V 1/16”

Coolidge’s family, in short, investigated their genealogy and showed keen interest in the possibility that they had Native American ancestors.

Of course, genealogical investigators of that era did not have access to DNA testing. So what does modern evidence tell us about President Coolidge’s ancestry?

Jennifer Coolidge Harville, the great-granddaughter of President Coolidge and Grace Coolidge, explored her ancestry by taking an autosomal DNA test through a leading genealogy company. She wasn’t looking to solve a historical mystery. “To be honest, I just wanted to find out my own background,” she says.

Harville reports that her results offer no evidence of Native American ancestry. The DNA testing shows that Harville can trace most of her origins to the British Isles, with scattered ancestry from the European continent. These findings align with the known Coolidge family tree. The first Coolidges to arrive in America—John Coolidge and wife Mary—came from Cottenham, England, in 1630. John and Mary Coolidge settled in Watertown, Massachusetts.

As Harville notes, however, Coolidge’s genealogical roots do not change the president’s record of working with Native Americans. The thirtieth president interacted with and supported indigenous people more than his twentieth-century White House predecessors did.

Jennifer Coolidge Harville, great-granddaughter of Calvin and Grace

Leading Eagle

Most notably, Coolidge supported the bill that made all Native Americans citizens of the United States. He signed the Indian Citizenship Act into law on June 2, 1924.

Hearing directly from a young Native American may have strengthened Coolidge’s support for the citizenship act. Writing for the White House Historical Association, scholar Colleen Shogan points to Coolidge’s December 1923 meeting with the Advisory Council on Indian Affairs, better known as the Committee of One Hundred. During that meeting, a Cherokee woman named Ruth Muskrat told Coolidge: “We want to become citizens of the United States, and to have our share in the building of this great nation, that we love. But we want also to preserve the best that is in our own civilization.”

The New York Times reported that Muskrat spoke “with such force and clarity” that “the Chief Executive invited her to take lunch with him and Mrs. Coolidge.”

In 1925 alone, Coolidge brought Native American delegations to the White House at least four times. Photos in the Library of Congress dated January 15, 1925, show Coolidge with members of the Osage tribe. The following month, the president welcomed a delegation of Plateau Indians. In March, Coolidge hosted twenty Sioux leaders, including, the New York Times said, “three Sioux chiefs who were a part of Sitting Bull’s band which massacred General Custer and his cavalry at Little Big Horn in 1876.” In May, another group of Sioux visited from South Dakota. After meeting with the visitors, Coolidge saw them gathering on the White House lawn for a photograph. According to the Times, “Mr. Coolidge quickly joined them, saying as he did so: ‘If you have no objection, I would like to pose with you.’ ”

Shogan notes the importance of these actions: “By inviting several Native American delegations to the White House and ensuring he was photographed with them, Coolidge successfully signaled his support of Native American citizenship and acknowledged the changing landscape of the nation’s pluralism.”

Coolidge had still more interactions with Native Americans—including his most famous—in 1927, when he situated the “Summer White House” in the Black Hills of South Dakota. He met with tribal leaders throughout that summer.

One meeting proved historic. On August 17, Coolidge became the first sitting president to make an official visit to a tribal reservation. (Chester Arthur had ridden a horse through the Wind River reservation.) Addressing ten thousand people at the Pine Ridge reservation, Coolidge began, “This is the first opportunity that has come to a president to speak especially to the Indians of America since the enactment of that epoch-making law which brought them all into a new relationship to the state and federal governments.”

Coolidge lamented past “injustice to the Indians.” He also acknowledged that issues remained. The president noted, for example, the “curious fact that most people in this country seem to believe that the Indians are a homogeneous people” when in reality “there are over two hundred tribes and bands in the United States, each with its own name, tongue, history, traditions, code of ethics, and customs.”

South Dakota’s Rapid City Journal reported that the scene “undoubtedly has no counterpart in United States history.” The Journal noted one reason the speech stood as a singular event: “Mr. Coolidge spoke as a chief of the Sioux Tribe.”

Indeed, less than two weeks earlier, on August 4, Sioux leaders had conferred on the president the title of “Leading Eagle.” In a ceremony with hundreds of Sioux tribe members, the leaders presented Coolidge with a headdress made of eagle feathers. Chief Yellow Robe said: “It is the greatest honor to the Sioux Tribe of South Dakota to import to you the emblem of the Sioux Nation in a war bonnet and to welcome you to our tribe. We name you Leading Eagle, ‘Wamblee-Tokaha.’ By this name you are to be known, King and the greatest Chief, which is signified by the bonnet and name you bear. Only a few of the greatest chiefs wear this double trail bonnet.”

The ceremony made front-page news around the country. Images of Coolidge in the headdress appeared in newsreels, newspapers, and even postcards. A wire-service reporter called this event “the greatest personal demonstration in [Coolidge’s] twenty years in public life.” Another reporter on the scene wrote that the president “appeared to be enjoying the happiest moment of his vacation when the bonnet had been placed on his head and adjusted by a member of the tribe.”

Coolidge surely derived as much satisfaction when Chief Yellow Robe told him, “You are now 100 percent American.”

Yellow Robe did not mean, of course, that Coolidge had pure aboriginal bloodlines. But in the end, it matters little whether Coolidge had Native American ancestry. Race, creed, and place of origin did not factor into Coolidge’s understanding of Americanism—his or anyone else’s.

“100 Percent Americanism”

Coolidge conveyed a perspective like that of Ruth Muskrat, who told the president that she and her fellow Native Americans wanted to become U.S. citizens but also “to preserve the best that is in our own civilization.” Once, when Coolidge introduced the Italian American portrait artist Ercole Cartotto to a diplomat, the diplomat asked, “Italian or American?” Answering for Cartotto, Coolidge said, “Both.” Coolidge later explained to the artist, “You can serve this land better and more by bringing to it the best you inherited.”

Coolidge made a similar point in his October 1925 address to the American Legion Convention. He said: “The bringing together of all these different national, racial, religious, and cultural elements has made our country a kind of composite of the rest of the world, and we can render no greater service than by demonstrating the possibility of harmonious cooperation among so many various groups. Every one of them has something characteristic and significant of great value to cast into the common fund of our material, intellectual, and spiritual resources.”

Coolidge urged his audience to “come to the sympathetic understanding that human nature is about the same everywhere, that it is rather evenly distributed over the surface of the earth, and that we are all united in a common brotherhood.” He explained, “We shall have to look beyond the outward manifestations of race and creed,” for “Divine Providence has not bestowed upon any race a monopoly of patriotism and character.”

The president added that as long as citizens remained devoted to “a standard of patriotic conduct and civic integrity,” Americans should have little “concern about differences of individual opinion in other regards.” Such differences, he said, “give variety to our tastes and interests” and “broaden our vision, strengthen our understanding, encourage the true humanities, and enrich our whole mode and conception of life.”

Coolidge summed up his perspective with this aphorism: “I recognize the full and complete necessity of 100 percent Americanism, but 100 percent Americanism may be made up of many various elements.”

This article appears in the Summer 2025 issue of the Coolidge Review. Request a free copy of a future print issue.