How 2 Presidents Saved the Declaration of Independence

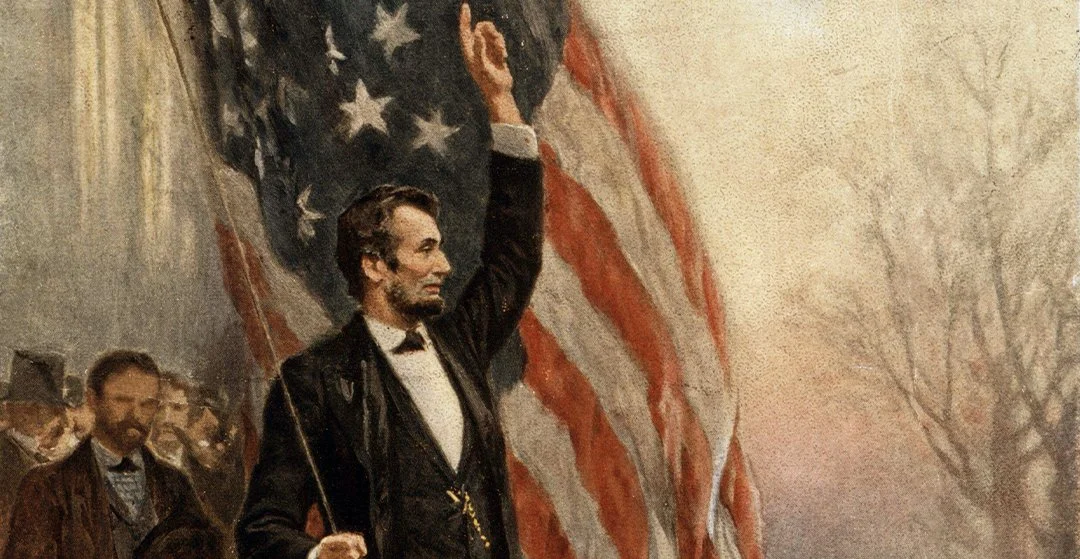

President-Elect Abraham Lincoln raising the American flag at Philadelphia’s Independence Hall, where he said, “I have never had a feeling politically that did not spring from the sentiments embodied in the Declaration of Independence”

(Alamy Stock Photo)

By Janice Rogers Brown

This article appears in the Summer 2025 issue of the Coolidge Review. Request a free copy of a future print issue.

In 2026 the United States will mark the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. A yearlong celebration of America’s beginnings seems right.

But the Declaration didn’t always earn such respect. For many years, it languished in obscurity. It was a letter that had served its purpose, a simple artifact. Few presidents paid it any special attention.

It took a national crisis and the eloquence of an Abraham Lincoln to transform the Declaration into the cornerstone of American ideals. Before and during the Civil War, Lincoln parsed the language of the Declaration to call attention to its moral principles. With the republic’s survival at stake, Lincoln identified the Declaration’s principles as the foundation of America’s constitutional order.

Sixty years after Lincoln’s death, another president confronted a threat to the republic. The challenge that Calvin Coolidge faced was more subtle than the one that Lincoln met, but it was insidious nonetheless.

Like Lincoln, Coolidge sought to defend the Declaration at a time when the nation’s founding principles were under assault.

Lincoln’s rhetorical efforts went to the heart and sinew of the Declaration. President Coolidge focused on the document’s spirit.

“THE FATHER OF ALL MORAL PRINCIPLE”

Long before Lincoln warned that “a house divided against itself cannot stand,” politically astute observers recognized the looming crisis. In 1816, Supreme Court justice Joseph Story expressed his well-founded fears in a powerful metaphor. Story wrote, “I have long inclined to the belief that the centrifugal force was greater than the centripetal” in our government. Thus, the danger was not that we would “fall into the sun, but that we may fly off in eccentric orbits, and never return to our perihelion.”

Throughout his career, Lincoln sought to restore public allegiance to the constitutional order. To do so, he explicitly linked the Declaration and the Constitution.

In 1861, in an impromptu speech at Philadelphia’s Independence Hall, President-elect Lincoln confessed, “I have never had a feeling politically that did not spring from the sentiments embodied in the Declaration of Independence.”

Lincoln passionately defended the Declaration’s principle of equality during his Senate campaign against Stephen Douglas in 1858. Douglas argued that the signers of the Declaration referred only “to white men, to men of European birth and European descent, when they declared the equality of all men.”

Lincoln rejected this claim. During a July 10 speech in Chicago, he said: “Let us discard all this quibbling about this man and the other man—this race and that race and the other race being inferior…. Let us discard all these things, and unite as one people throughout this land, until we shall once more stand up declaring that all men are created equal.” Lincoln called the Declaration’s insistence on the equality of all men “the father of all moral principle.”

The next year, in a letter reflecting on the anniversary of Thomas Jefferson’s birth, Lincoln wrote:

All honor to Jefferson—to the man who, in the concrete pressure of a struggle for national independence by a single people, had the coolness, forecast, and capacity to introduce into a merely revolutionary document, an abstract truth, applicable to all men and all times, and so embalm it there, that to-day, and in all coming days, it shall be a rebuke and a stumbling block to the very harbingers of re-appearing tyranny and oppression.

Lincoln showed his commitment to this abstract truth in the Gettysburg Address. America, he said, was “conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” The Civil War, he said, was a test not just for America but for “any nation so conceived and so dedicated.”

The political philosopher Harry Jaffa notes that Lincoln’s interpretation of “all men are created equal” transformed that proposition from a “pre-political, negative, minimal” norm that “prescribes what civil society ought not to be” into “a transcendental affirmation of what it ought to be.”

At Gettysburg, Lincoln called for “a new birth of freedom.” That new birth came with the end of the Civil War and the ratification of Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution. Those amendments gave legal force to the moral principle at the heart of the Declaration.

THE FINALITY OF THE DECLARATION

By the time Coolidge assumed the presidency in the 1920s, progressivism, Darwinism, and materialism had begun to dim the luster of the Declaration’s natural law telos. President Coolidge took the opportunity of the Declaration’s 150th anniversary to illuminate the charter’s relevance for the America of his or any era.

In his 1926 speech at Independence Hall, Coolidge acknowledged that the right of people to choose their own rulers was an old idea—detailed by the Dutch as early as July 26, 1581, and by the British people in their long struggle with the Stuarts. But he insisted that “we should search those charters in vain for an assertion of the doctrine of equality.” It was this equality principle that Coolidge deemed “profoundly revolutionary.”

The Declaration mattered, Coolidge said, not because it established a new nation but because it established “a nation on new principles.” The Declaration’s preamble set out “three very definite propositions” regarding “the nature of mankind and therefore of government”: “the doctrine that all men are created equal, that they are endowed with certain inalienable rights, and that therefore the source of the just powers of government must be derived from the consent of the governed.”

“Great ideas do not burst upon the world unannounced,” Coolidge said. “They are reached by a gradual development over a length of time usually proportionate to their importance.” To the president, the conclusion seemed inescapable that the Declaration’s principles grew out of “the religious teachings of the preceding period.” Those “principles of human relationship” were “found in the texts, the sermons, and the writings of the early colonial clergy,” who were earnestly instructing their congregations “in the great mystery of how to live.” Coolidge observed: “They preached equality because they believed in the fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man. They justified freedom by the text that we are all created in the divine image, all partakers of the divine spirit.” The founding generation, he explained, “came under the influence of a great spiritual development and acquired a great moral power.”

Unlike Lincoln, Coolidge was not concerned with fending off attacks on the Declaration’s language. Instead, he cautioned would-be innovators who would discard the Declaration’s principles:

It is often asserted that the world has made a great deal of progress since 1776, that we have had new thoughts and new experiences which have given us a great advance over the people of that day, and that we may therefore very well discard their conclusions for something more modern. But that reasoning cannot be applied to this great charter.

About the Declaration’s meaning Coolidge expressed no qualms:

If all men are created equal, that is final. If they are endowed with inalienable rights, that is final. If governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed, that is final. No advance, no progress can be made beyond these propositions. If anyone wishes to deny their truth or their soundness, the only direction in which he can proceed historically is not forward, but backward toward the time when there was no equality, no rights of the individual, no rule of the people. Those who wish to proceed in that direction cannot lay claim to progress. They are reactionary.

Coolidge ended his speech by declaring that “the things of the spirit come first” and warning that the failure to understand this aspect of the Founding would cause the American project to fail. This admonition was not a rhetorical flourish. It provides the key to understanding the perils that Coolidge saw threatening human flourishing.

In addition to challenging the premises of progressivism, President Coolidge took on the materialism of his age. The Declaration, he said, was “a great spiritual document.” He explained: “Equality, liberty, popular sovereignty, the rights of man—these are not elements which we can see and touch. They are ideals.” The president added, “Governments do not make ideals, but ideals make governments.”

Coolidge cautioned Americans not to sink into materialism. Unless Americans remembered the things of the spirit, he said, “all our material prosperity, overwhelming though it may appear, will turn to a barren sceptre in our grasp.”

President Coolidge understood that “a spring will cease to flow if its source be dried up; a tree will wither if its roots be destroyed.” Without enduring faith, the principles of the Declaration perish. Materialism is not enough. If you want liberty, something more awesome, powerful, glorious, and worthy of reverence is required.

Janice Rogers Brown served as a judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit from 2005 until she retired from the bench in 2017.

This article appears in the Summer 2025 issue of the Coolidge Review. Request a free copy of a future print issue.