Jefferson Overruled

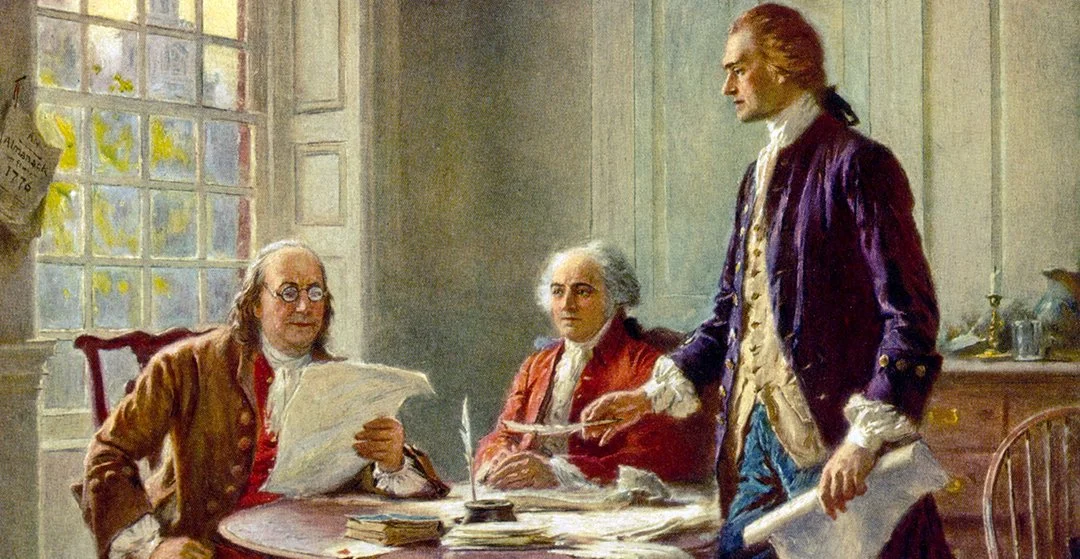

Thomas Jefferson shares his draft of the Declaration of Independence with Benjamin Franklin and John Adams (Wikimedia Commons)

By J. French Hill

This article appears in the Summer 2025 issue of the Coolidge Review. Request a free copy of a future print issue.

Thanks to Benjamin Franklin’s “Poor Richard,” for two decades every member of the Continental Congress was well aware that “haste makes waste.” But the days of late June and early July 1776 cast doubt on the universality of Franklin’s prudent proverb.

By that spring, the colonies had moved closer to independence. Individual colonial assemblies had developed their own list of grievances and calls for independence, many patterned on Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of the Causes and Necessity for Taking up Arms from the previous year, and on his mass-distributed 1774 pamphlet, A Summary View of the Rights of British America. Colonies were also drafting their own state constitutions to be adopted in a free United States of America.

Jefferson had sequestered himself at his beloved Monticello, suffering from migraines. No doubt the stresses of drafting ideas for Virginia’s constitution and grieving the loss of his mother, who died at the end of March, contributed to his condition. But in May, he descended from his Olympus and made the ten-day journey to Philadelphia to join the Second Continental Congress. He originally found rooms in the city center, but by May 23, Jefferson and his fourteen-year-old slave, Robert Hemmings, had found quieter quarters in the Graff House at Seventh and Market Streets. Jefferson had with him his recently acquired writing desk and Windsor chair.

On Friday, June 7, Richard Henry Lee, Jefferson’s fellow Virginia delegate, presented to the Congress Virginia’s resolution on independence: “these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States.” During debates on the Lee Resolution on Saturday and Monday, John Dickinson of Pennsylvania, Robert Livingston of New York, and Edward Rutledge of South Carolina argued that the colonies were not ready for independence. Samuel Adams and his cousin John took the other side, stating that the citizens were “eager” and “ahead of Congress” on independence. A nonbinding vote in the Committee of the Whole found seven of thirteen colonies in favor of declaring independence.

On Tuesday, June 11, Congress appointed the Committee of Five to draft a declaration to unite the colonies, bind the delegates, and inform the world of America’s intent. The committee included Jefferson, John Adams, Roger Sherman, Franklin, and Livingston, who had questioned only the timing of declaring independence.

From this crew, the job of drafting fell to Jefferson. The Virginian set to work.

Jefferson was well suited to the task. He possessed an encyclopedic understanding of British, French, and classical political philosophy. He could draw on his published Causes and Necessity and Rights of British America, as well as his three recent drafts of the Virginia constitution.

It helped, too, that the Pennsylvanian Gazette published the Virginia Declaration of Rights, which George Mason had drafted and which the House of Burgesses adopted on June 12. Mason’s document said that “all men are by nature equally free and independent and have certain inherent rights,” including “the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.”

Jefferson holed up in the Graff House to labor over a draft declaration. We can picture him by the second-floor window on Market Street—writing, crossing out, perfecting. After a week of sipping tea, toiling at the new Randolph desk, and singing and humming to himself, Jefferson put down his quill. He shared a rough draft with Adams and Franklin on Wednesday, June 19.

The Edits Begin

The Sage of Monticello was miserable for the next ten days as first the committee and then the whole Congress reviewed and debated his draft declaration.

First to strike were Adams and Franklin. Adams believed Jefferson went too far in portraying King George III as a “tyrant,” though he offered no edit. He switched “colonies” to “states” to clearly note America’s status change. He also suggested a new grievance about forced change in venue of the colonial legislatures. Franklin, one of America’s most revered editors and printers, made seven changes and corrected grammar and spelling.

The most significant edits at this stage came from Jefferson himself. He added such memorable phrases as “dissolve the political bands,” “separate and equal,” and “endowed by their Creator.”

On Friday, June 28, Congress convened to hear Jefferson read the draft. But the delegates tabled discussion of the declaration until they could vote on the Lee Resolution. The Congress debated whether to declare independence that Monday, July 1, and the following day. Finally, on July 2, Congress took the momentous vote and approved Lee’s call for independence.

Jefferson’s Section on Slavery

Former House Speaker John Boehner used to say, “Congress moves very slowly until it doesn’t.” The two days after the vote on independence proved Boehner right. This period also showed why Franklin’s aphorism “haste makes waste” isn’t always on point.

First, the Committee of the Whole removed Jefferson’s entire passage on the slave trade, over strong objections from Georgia and South Carolina. Jefferson’s draft had referred to slavery as a “cruel war against nature itself.” It had also accused King George of blocking colonial efforts to end the slave trade—“this execrable commerce”—and of “exciting those very people [the enslaved] to rise up in arms against us.” The historian Joseph Ellis characterizes Jefferson’s depiction of slavery this way: “Since the colonists had nothing to do with establishing slavery—they were the unfortunate victims of English barbarism—they could not be blamed for its continuance.”

Congress apparently saw the twisted logic and hypocrisy, as well as the economic considerations involved, and pulled out Jefferson’s section on the slave trade. As for the claim to that the king urged revolts, the Committee of the Whole restated the grievance to say that he had “excited domestic insurrections among us,” which delegates understood as a reference to both Indians and slaves.

The delegates also took issue with the section of the Jefferson draft that said the colonies achieved success “at the expense of our own blood & treasure unassisted by the wealth or the strength of Great Britain.” In other words, the Americans owed nothing to advantages or protections afforded by the strength of the Mother Country.

This line reprised a claim that Jefferson had made in Causes and Necessity: “In our own native land, in defense of the freedom that is our birthright, and which we ever enjoyed till the late violation of it—for the protection of our property, acquired solely by the honest industry of our forefathers and ourselves—against violence actually offered, we have taken up arms.” And in the Rights of British America, he wrote, “America was conquered, and her settlements made, and firmly established, at the expense of individuals, and not of the British public.”

Jefferson seemingly forgot the tiny detail that the British had driven the French from North America.

The delegates recognized that the draft went over the top, replacing Jefferson’s language with a line saying that the Americans had reminded the British of “the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here.”

Throughout his draft, Jefferson worked to build a convincing case that American colonists had no choice but to declare independence over the usurpations of the king, Parliament, and, by extension, the British people. The Committee of the Whole chose to soften the tone criticizing the British people.

The delegates believed it sufficient to declare that our “British brethren” had been “deaf to the voice of justice and consanguinity.” The Congress removed language saying that the Americans felt compelled “to renounce for ever these unfeeling brethren,” as well as this Jefferson line: “We might have been a free and great people together.”

Jefferson resented the changes the Committee of the Whole made to the Declaration of Independence. As he later recounted, “I was not insensible to these mutilations.” He copied his earlier draft and shared it with friends, including Richard Henry Lee, who had sponsored the resolution of independence. On studying Jefferson’s copy, Lee said he wished “that the Manuscript had not been mangled as it is.”

A Group Edit That Worked

As the Committee of the Whole revised the draft declaration, Franklin, sitting near Jefferson, noted the younger man’s frustration. He then told the moping Jefferson the story of one John Thompson.

It seems Mr. Thompson was setting up his own shop and proposed to have a sign painted with the words “John Thompson, Hatter, makes and sells hats for ready money,” along with an illustration of a hat. Franklin said that friends offered Thompson advice. One suggested removing “Hatter,” since the sign already said “makes hats.” A second told him to take out “makes”; customers wanted hats and didn’t care who made them. A third proposed dropping “for ready money,” because stores in the area didn’t sell on credit. A fourth took issue with the word “sells.” After all, no one would think Thompson was giving away hats.

And so, in the end, the sign simply said “John Thompson” and featured a picture of a hat.

The story does not seem to have done much to improve Jefferson’s spirits. But contrary to the complaints of Jefferson and Lee, the Committee of the Whole did not “mutilate” or “mangle” the Declaration of Independence. As the historian Pauline Maier aptly notes in her book American Scripture, “This was no hack editing job.” The committee’s changes made Jefferson’s draft stronger, eliminated “outlandish assertions,” and more clearly articulated the views of the entire assembly. The revisions to the Declaration managed “to enhance both its power and its eloquence.”

It was, Maier concludes, “an act of group editing that has to be one of the great marvels of history.”

J. French Hill represents the Second District of Arkansas in the U.S. House of Representatives. He chairs the House Financial Services Committee.

This article appears in the Summer 2025 issue of the Coolidge Review. Request a free copy of a future print issue.